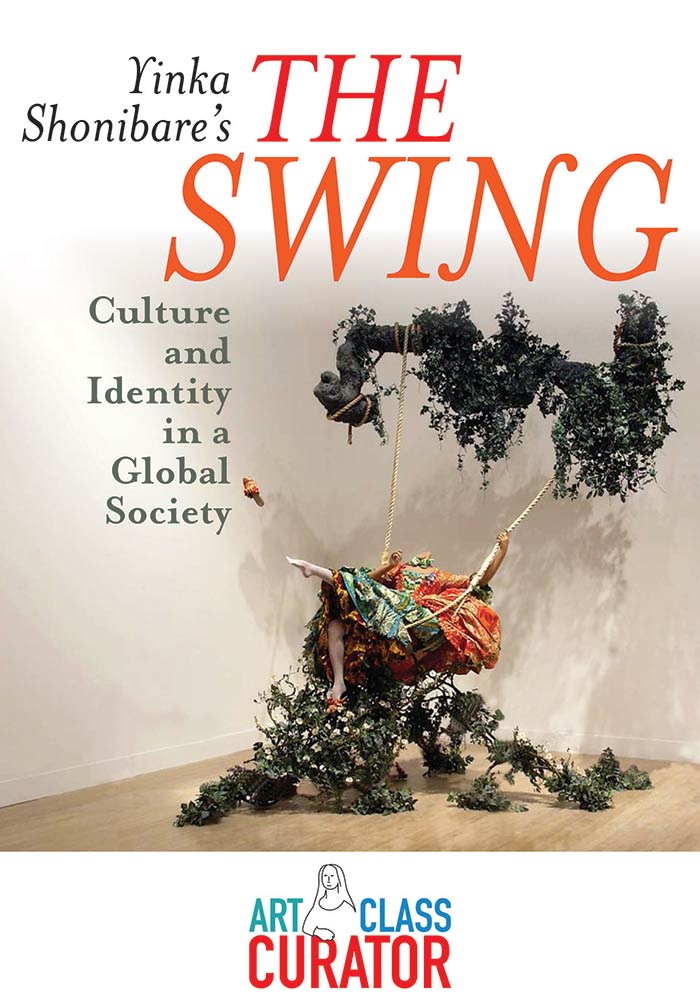

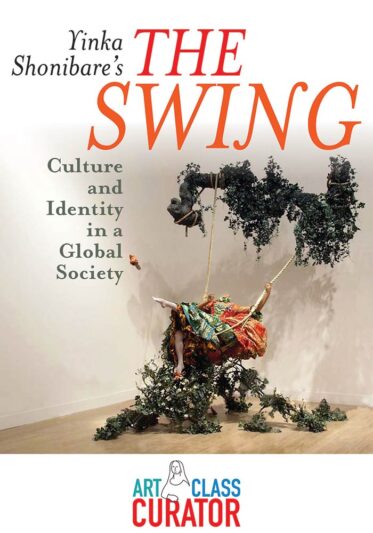

Inside: Comparing Yinka Shonibare The Swing (after Fragonard) with the original painting and exploring the commentary on race, class, and multiculturalism.

The Swing is Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s best known work and is an icon of the Rococo style. It’s a painting that’s so familiar, it can be easy to pass it by without considering the details or the story behind it. Yinka Shonibare, a bi-cultural artist whose work explores issues of race, class, and colonialism, recreated the famous artwork and gave us a lot more to think about.

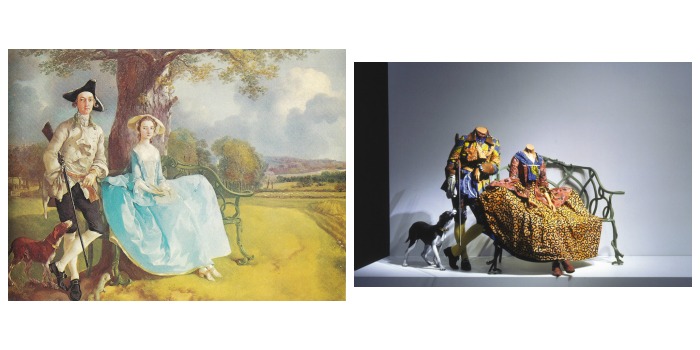

Fragonard’s original painting depicts a lavishly dressed young woman swinging with the help of a man in the shadows while another man looks up at her from below. Symbolic statues watch in the lush outdoor setting and the man below is well placed to look up the woman’s skirts. The woman is looking at the man while one of her shoes is flying over his head, seemingly flung from her foot. The artwork is rumored to have been commissioned by a man who wanted a painting of himself and his mistress, a detail which adds an interesting layer to the original title of the painting, The Happy Accidents of the Swing.

The Swing (after Fragonard)

Yinka Shonibare The Swing (after Fragonard) features a lifesize, three-dimensional recreation of the woman on the swing with some of the surrounding foliage, but there are many notable differences. The eloquent dress is made with bright African wax prints (that aren’t exactly African) that are branded with a fake Chanel logo. The mannequin skin tone is brown rather than white.

And, oh, she’s headless.

Yinka Shonibare The Swing (after Fragonard) was not the first or last Rococo artwork the artist took a guillotine to.

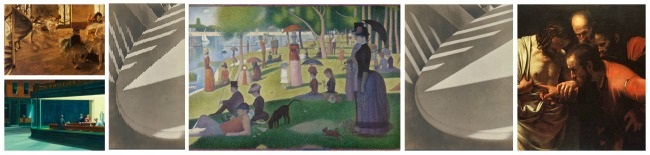

Thomas Gainsborough, Mr and Mrs Andrews, 1750 beside Yinka Shonibare, Mr.and Mrs. Andrews without their Heads, 1998

Henry Raeburn, The Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch, 1790s beside Yinka Shonibare, Reverend on Ice, 2005

It’s worth pointing out that The Swing became a hallmark of the frivolity and wealth that philosophers in the Age of Enlightenment abhorred, and less than 30 years after Fragonard finished his painting, the French Revolution began claiming the heads of many in the aristocracy.

Shonibare’s version invites us to consider who society allows to be light-hearted, the trappings of sexism, racism, and classism, and the status symbols we use as a cultural shorthand to tell us who is important.

Much of how we define ourselves is determined by how society sees us and most people don’t take more than a glance. Our gender, the color of our skin, the clothes we wear, and the activities we take part in speak for us. Without our voice, without our heads, what do our bodies say?

Pattern in Yinka Shonibare Artworks

In addition to the beheading, another key change in Shonibare’s recreation is his use of color and pattern in the fabrics. When researching the work of Shonibare, I discovered these fabrics that we would usually associate with Africa did not originate in Africa. These “Dutch wax” fabrics were originally created in England and Holland, and they were sold to people in Africa after selling them in Indonesia failed. These fabrics became an integral part of African culture, and Shonibare found that duality of cultural identity interesting. He said, “But actually, the fabrics are not really authentically African the way people think. They prove to have a crossbred cultural background quite of their own. And it’s the fallacy of that signification that I like. It’s the way I view culture—it’s an artificial construct.”

Free Poster

What Do Kids Learn from Looking at Art Poster

Our students learn so much from looking at art. Use this poster in your classroom to remind them of all the skills they’re growing!

Identity in a Global World

Shonibare was born in London and grew up in both Nigeria and the United Kingdom. When asked about multiculturalism, he said, “In a diverse society, people have to find a way of being together, and that can only come from understanding other cultures. Otherwise, you’re just fighting for space.”

Yinka’s work asks us to think about how identities are constructed in today’s global society. This is an essential question for all of us, but especially the youth who are discovering and sculpting themselves for the first time. In a society that often reverts to ‘us versus them’ and prizes the individual over the collective, it is vital for our students to actively participate not only in the creation of their personal identity, but in the building of a shared, inclusive community identity. Comparing Yinka Shonibare The Swing (after Fragonard) with the original can help them do that.

Discussion Questions

Use Yinka Shonibare The Swing in your classroom with the following discussion questions.

- What’s going on here? What do you see that makes you say that?

- How does this artwork merge different cultures?

- How are the mood/emotions different from this artwork to Fragonard’s version?

- Why do you think this artist choose to depict this artwork as a sculpture?

- Why did the artist choose to decapitate the figure?

Classroom Connection

The compare and contrast art activity from the bundle of free art appreciation worksheets is a great way to get students thinking. This would be a great artwork for older students to write about, especially when they’re studying the history of the 1700s. Putting this artwork with others that show the duality of culture and reference colonization and class systems would open up the educational possibilities.

Free Worksheets!

Art Appreciation Worksheets

In this free bundle of art worksheets, you receive six ready-to-use art worksheets with looking activities designed to work with almost any work of art.

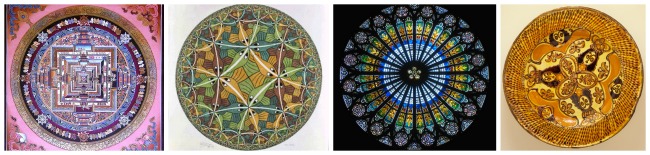

Radial Balance in Art Examples

Radial Balance in Art Examples