“Welcome to the Art Show!”

“Welcome to the Other Art Show!”

“Welcome to the Other Other Art Show!”

So state the signs on three walls of our townhome, most of which are covered with our five-year-old daughter’s artwork. The “every wall is an art gallery” decorating scheme is not for everyone: it’s cluttered and colorful, occasionally weird. But in a small house, especially, concessions must be made for kid-friendly space, and lines blur between living and playing and learning. And we draw, paint, and/or make something just about every day, including more ephemeral creations in Play-doh, blocks, and, occasionally, pantry items.

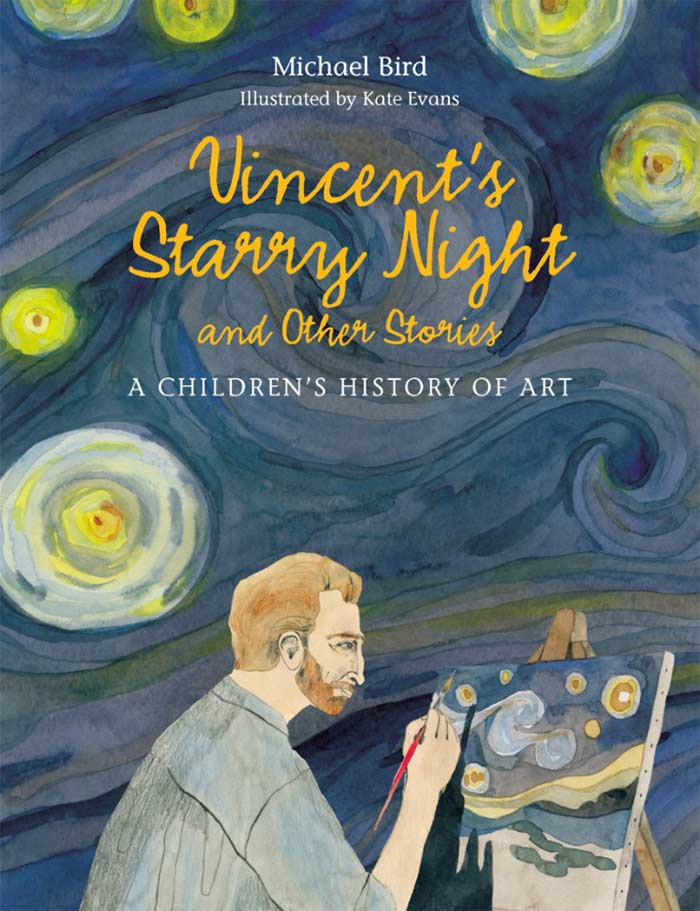

Yesterday, powdered cinnamon played a central role in our art-making (it smelled like autumn – bonus!) The inspiration was an early entry in the recently published book Vincent’s Starry Night and Other Stories: A Children’s History of Art, written by Michael Bird and illustrated by Kate Evans. At home or in the classroom, the book beautifully brings together story and art.

Please note, this post includes Amazon affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

This book is great intersection of passions for us, because if there is one category that outpaces art-making in our house, it’s stories – and this book combines both. (Overlapping categories…ah, a theme we know well, says a countertop currently housing a Lego building, a stone-polishing project, a drying button bowl, and pita bread in progress.) The book offers short stories about artworks, artists, and eras that are great for combining art and story.

Vincent’s Starry Night and Other Stories takes a narrative approach to a world art survey, prehistoric past to present. Sixty-eight short chapters comprise this dense world art tour (heavy on the Europeans, it must be noted, but including more than a half-dozen Asian, Latin American, Middle Eastern, and African artists and cultural traditions). Perspectives and approaches change with each entry, making each a surprise in approach and content. Integrating literacy and art, each entry brings to life artists and their art with personal stories set in broader historical and cultural contexts. I was surprised to learn something new with every entry! The stories skew toward middle- to older-elementary school-aged children (the book listings state that it’s for ages 8-14) but my kindergartner kept up and enjoyed looking for artists she knew. Learning through story about artists and their inspirations also prompted her own explorations.

In the second chapter of the book, we read that women and children took part in making early cave art, as determined by the size of painted handprints in Chauvet Cave, France (dated to 32,000-30,000 BCE). Prehistoric people painted their palms to create traditional prints, and made reverse outlines by mixing dirt in their mouths and spit-blowing it over their hands. We decided to try our hands – literally – at making similar outlines. We brainstormed ideas for materials – powdered tempera color, whole wheat flour, sugar (my daughter’s favorite) – and settled on cinnamon as our “paint.” The shaker on the spice container would dispense it nicely. But how to get the cinnamon to stick to the cardboard so we could see the results? Vegetable oil! We couldn’t find a cave, more’s the pity, and my partner was not in favor of applying spices to the walls, so we used thin packaging cardboard as our canvas (white on one side and kraft-paper brown on the other).

It was fun to experiment, to discuss whether and what we would consider putting in our mouths to blow against our hands to create the reverse print, as did our cave art ancestors of thirty thousand years ago. My kid was still sure she would use sugar for such a technique.

Given her age, my daughter was drawn less to overviews about eras and places (the Parthenon in Athens is a lovely page, though, and she did enjoy the map of Paris because she recognized numerous landmarks). But the book is both reference and storybook, describing methodologies and history inside of character-driven short narratives. We both enjoyed a story about a Yoruba girl whose skilled metalsmith father is making a bronze head sculpture of a king. I learned about casting methods, and my daughter cheered on Abebi, a girl who wanted to become an apprentice, like her brothers, in a male-dominated art.

As a former media and communication professor, I was happy to see a nod to Eadweard Muybridge, who created the zoetrope (or “zoopraxiscope” as he called it) – an introduction to film aa art. My daughter immediately understood that Muybridge’s “A Horse in Motion” was like her GoldieBlox “Movie Machine.” Connections like these are moments that I live for – not because I’m trying to raise a future Jeopardy! contestant, but because I’m thrilled about the opportunities in creative STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art, medicine) thinking for hands-on learning.

The informative stories in this book do so in narrative form, requiring attention to contextual information. For the intended audience, this is a welcome strategy – a different format than many contemporary art history books intended for children, which tend to organize information into fact blurbs. The stories and illustrations in Vincent’s Starry Night require attention to detail, to making guesses and asking questions about time period, society, personalities, the role of artists and artisans in sharing culture, mediums, etc.

Not all of the stories are happy ones; Jacques-Louis David’s paintings during the time of the French revolution were a bit too grim to read aloud just yet, as was the following entry about Goya’s work in documenting war scenes. We discussed the challenges that women have faced as artists when reading the chapters on painter Berthe Morisot and sculptor Camille Claudel. Several stories left my daughter and I feeling cut off, with less resolution to understanding than is usually comfortable in stories for children. But that’s okay, too – there is conversation to be had about understanding stories in their historical context. We also talked about point of view in stories and in art, because the narrative voice changes in these stories.

I would love to know how long it took illustrator Kate Evans to produce her lovely watercolors this book. Her understated colors and textures give the stories a through-thread even as narrative voices, geography, time periods, and cultural contexts change, weaving a sense of connection through this broad survey.

The last chapter, about Ai Weiwei’s sunflower seeds, provided a wonderful opportunity to talk with my daughter about the eternal question “What is art?” and to explore more about processes of making art. (How many people does it take to paint tens of millions of tiny porcelain sunflower seeds? Oh, around 1,600! People in the small Chinese city of Jingdezhen who helped in any of the nearly 30 steps required to create the small seed sculptures will not soon forget the experience!) We decided to try to create a few sunflower seeds of our own with a quick-dry sculpting medium. Making the simple shape was more difficult than I anticipated – Ai Weiwei’s team used molds for the porcelain – but we made a half-dozen seeds and tried decorating them with black markers, watercolor pencil, and tempera paint. So many entry points into one work, with one story.

To quote Ai Weiwei, “Art is a tool to set up new questions…” And this book sets up familiar and new questions in accessible ways.

I always jump at new books about art and artists when I spot them in our local library, and Vincent’s Starry Night and Other Stories takes its place among beautiful books from the past few years that we’ve renewed again and again:

- Dorothea’s Eyes, written by Barb Rosenstock and illustrated by Gerard DuBois

- Balloons over Broadway: The True Story of the Puppeteer of Macy’s Parade by Melissa Sweet

- Matisse’s Garden, written by Samantha Friedman and illustrated by Christina Amodea, with artwork by Henri Matisse (I also like Jeanette Winter’s Henri’s Scissors)

- Cloth Lullaby: The Woven Life of Louise Bourgeois, written by Amy Novesky and illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault

- A Splash of Red: The Life and Art of Horace Pippin, written by Jen Bryant and illustrated by Melissa Sweet

- Jake Makes a World: Jacob Lawrence, a Young Artist in Harlem, written by Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts and illustrated by Christopher Myers

- Kid Artists: True Tales of Childhood from Creative Legends, written by David Stabler and illustrated by Doogie Horner

- Me, Frida, written by by Amy Novesky and illustrated by David Diaz (the paperback edition was published last year)

- A World of Your Own by Laura Carlin

Rachel Lapp Whitt is a designer and editor currently in Illinois who works with clients of all sizes, from small businesses to national health care companies, bloggers to bed-and-breakfasts, nature centers to recording artists. She previously worked as a journalist and in public relations, and taught college-level Communication and Media courses emphasizing multicultural and feminist studies. Her great love is her daughter, and then coffee, children’s books about artists and women making history, street art, outsider art, design and art blogs, cooking shows, and a refill on that coffee.

Leave a Comment