Some pieces of art just make you uncomfortable. Maybe it’s a movie or scene that hits too close to home, or a book about a particularly violent event (real or fictional) that makes you squirm… or a painting that brings up regrets or painful memories.

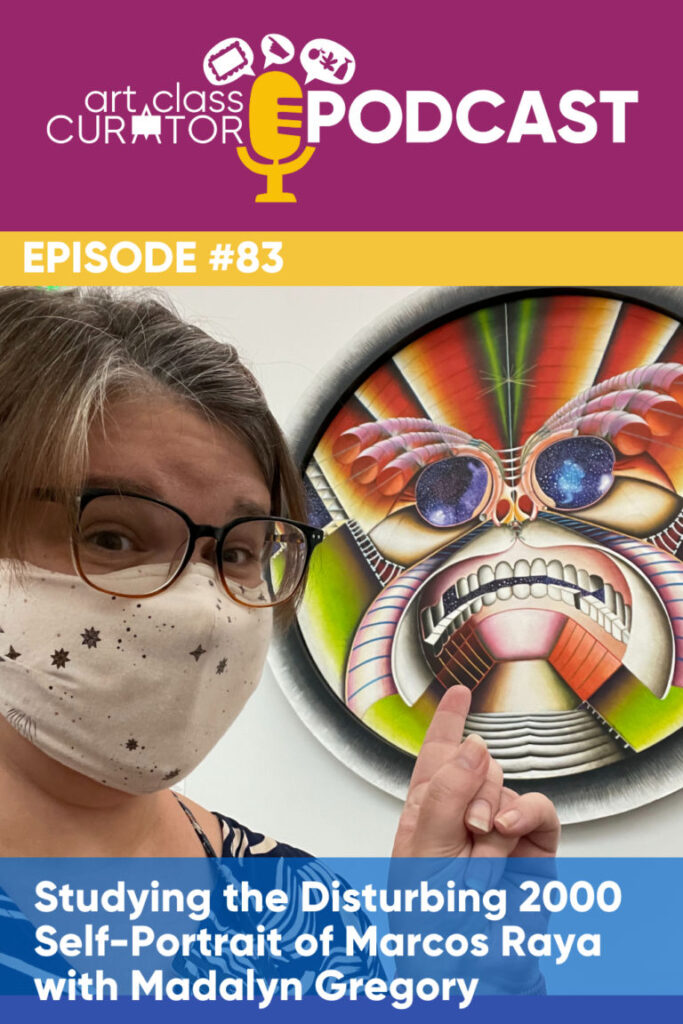

For Madalyn Gregory and myself, Marcos Raya’s 2000 painting The Anguish of Being and the Nothingness of the Universe made us feel ill at ease. So of course we had to discuss it! I’m excited to welcome Madalyn back on the show to talk about art. In this episode, we describe and interpret Raya’s piece, making personal connections along the way that surprised even me.

1:14 – A description of Raya’s self-portrait

6:13 – Our initial reactions to the artwork and the various connections we see in the details

10:30 – How the painting puts the mundane of day-to-day life in perspective

13:37 – How Raya’s work reflects the messiness and complexity of life and space

17:46 – Madalyn shares an interpersonal interpretation of the throat area’s depiction

19:44 – The contrast between the cleanliness of the painting and the message it conveys

23:51 – A possible double meaning behind the cardboard imagery

30:55 – Another interpretation of the cardboard detail and how it relates to our life experiences

38:59 – The very personal realization that brought back my discomfort with the artwork, just as I started feeling more at ease with it

44:48 – The necessity of allowing your kids (and others) to see the humanity in you

48:26 – Madalyn and I discuss the depressive title of Raya’s self-portrait

51:55 – How my views changed on the artwork from beginning to end of this conversation

- Free Lesson Sample

- The Curated Connections Library

- Drawing Description Game

- Episodes 60 and 61 with Madalyn

Be a Podcast Guest: Submit a Voice Memo of Your Art Story (Scroll to the bottom of the page to submit your story.)

Cindy Ingram: Hello and welcome to The Art Class Curator Podcast. I am Cindy Ingram, your host and the founder of Art Class Curator, and The Curated Connections Library. We’re here to talk about teaching art with purpose and inspiration from the daily delights of creativity to the messy mishaps that come with being a teacher. Whether you’re driving home from school or cleaning up your classroom for the 15th time today, take a second, take a deep breath, relax those shoulders, and let’s get started.

Hello everybody. I am so excited to welcome Madalyn Gregory back to the podcast. Hi, Madalyn.

Madalyn Gregory: Hello.

Cindy Ingram: We are today going to do another art discussion, art conversation. We have done one in the past. You can go back and check that out. We talked about Death and Life by Gustav Klimt. Today, we’re going to talk about The Anguish of Being and the Nothingness of the Universe by Marcos Raya. I thought we would start by just describing it for the listeners. We will put this in the show notes, so you can go onto the show notes and check out the image of the artwork when you’re not driving but Madalyn, you want to start with a description?

Madalyn Gregory: Oh, man. There’s so much. It is circular. I don’t have a good gauge of how big it is.

Cindy Ingram: It’s big. I saw it in person this weekend at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. It was bigger than I expected it to be.

Madalyn Gregory: It says 176.5 centimeters overall.

Cindy Ingram: My American brain does not understand that. About 70 inches.

Madalyn Gregory: 70 inches, okay, yeah, that’s bigger than I am.

Cindy Ingram: It’s exactly my height. No, it’s 5’3. I’m 5’8 but that’s not 5.8. It’s different. Anyway, we’re rambling. It was big. It was way bigger than I expected.

Madalyn Gregory: Wow, that’s cool. Like I said, it is circular around the border. Just because that’s simple, I’ll go there first. It has a black circle, then it fades out to white but in the center, there is this strange majestic being. It reminds me of a skeleton, especially around the nose and the mouth, it almost looks like teeth but then his eyes are open sockets that have stars, the universe, and celestial things going on. There’s these canonical eyebrows, I guess you could say. There are three layers on each eye and there’s also a couple that come down around his mouth, almost like a mustache, then behind him, I don’t know if you’d call it hair or if it would be like an outfit of some kind but it goes up in orange, yellow, green, and a little bit of white, like shoots, this is a really hard one to describe.

Cindy Ingram: Enjoying it.

Madalyn Gregory: Because there’s also an edge because on the side where his neck would be, there’s green but there’s an edge that follows it that looks like cardboard to me, like whenever you look at the side of a cardboard, the edge. It looks like a being but it could be like a spaceship opening. It’s very strange, ethereal, and amazing. That was super probably not helpful.

Cindy Ingram: No, that was. I should have not been looking at it as you said that because I was trying to imagine if I had never seen this, what I would have thought of your description. To me, it looks like you’re looking into your ear in the skeleton’s head. You are the skeleton because it’s you looking out through his eyes. There I go saying “his” again but I guess the artist is he. This is potentially representing him. Then the mouth curve, it’s a concave. We’re both doing hand gestures.

Madalyn Gregory: Totally not helpful.

Cindy Ingram: Just imagine my hand is doing emotion. We’re inside his head essentially. Their heads. Just go to the show notes and look at it if that doesn’t make any sense because it’s a good description. As you were talking, I was like, “This one would be good for the drawing description game because I never thought about that with this artwork before but this would be really fun to describe.” If you all don’t know that listening, you have one student describe the artwork and the other student draws it based on the description. Maybe the listeners, before they check out the show notes, should go back and listen to your description, then draw it, then see what happens, then they can send it to us in the email.

Madalyn Gregory: Oh yeah, that would be amazing because this will come up with all sorts of things but it reminds me almost like a 60s sci-fi movie poster. I keep thinking of 2001 or something, which was much more minimalistic than this is. It’s very cool.

Cindy Ingram: I can see that reference too, especially because of the roundness. In 2001, they had the house, this round light thing. What do you think it means?

Madalyn Gregory: Oh man, I have so many thoughts and so many tangents that my brain could go on, especially now that you’ve said it’s like we’re looking through their head almost or their body. Like you said, the teeth are concave too. You really are stepping into this. It makes me think of other people’s perspectives but it also makes me think because it looks so alien, because we’ve got the stars, and all that, it makes me wonder about the wider perspective of the universe. I have a tattoo of Orion, the constellation, on my arm. The reason I did that was because it helps me remember that there’s a bigger life out there. There are bigger worlds. There’s other people. There are other planets. Who the heck knows? Put things in perspective. That’s really my initial reaction to this is to just try to remember everything.

Cindy Ingram: I love that.That’s really what I see in this too. I especially see the connection between the personal and the universal because most of the canvas is him or them inside. Because it feels like it’s me, so most of it is the person. We see the universe through the glasses. We see the universe just through the teeth, then also along the side but then the rest of it is presumably the inside of this person’s skull. We’re seeing color, we’re seeing tubes, we’re seeing patterns, and we’re seeing these little eye-shaped things. I don’t know if those are like bones or stitches or something. We’re just seeing all of this stuff going on the inside. It feels to me like some representation of a mental health issue. Some disturbance inside the brain. It just doesn’t feel like very, very peaceful inside this head.

Madalyn Gregory: Yeah, I can totally see that because the colors are really rich but it’s off-putting. It’s like watching a surgery video. Sometimes, I remember I have a skeleton and I get a real freak out. I think we can walk around feeling we are our thoughts, we’re what we do but we’re a sack of meat to a certain extent. I see that here. We didn’t mention it but there’s this line that goes up from the nose area up to the top, the border. It looks like there are lines that crisscross about halfway between. It looks almost like a line drawing of a star or like a dandelion. Sometimes, you’ll see it drawn that way. I feel like that connects to what you were saying with the mental health part, maybe where the brain would be and the spark of everything that we are.

Cindy Ingram: You know what that also could be is the third eye?

Madalyn Gregory: Oh, yes.

Cindy Ingram: It’s a symbol for intuition. I’m wondering if that line is maybe us seeing through space too. Maybe the light is breaking through from the stars into his head.

Madalyn Gregory: That almost makes me think like the Big Bang, the moment of creation, and all that. It’s just right there, following us through.

Cindy Ingram: It’s like in your own head, you’re wrapped up in your issues, your thoughts, your stories, your anxieties, your day-to-day life. It feels really all-encompassing. It feels really overwhelming. Especially, when you’re happy, going through a rough patch, it feels really cloudy. I’m talking from my own personal experience. I think that this really captures that really well.

Madalyn Gregory: It reminds me of the quote, “You are the sky. Everything else – it’s just the weather.” Pema Chödrön said that. I believe that she’s a Buddhist monk. I could have that wrong but “You are the sky. Everything else – it’s just the weather.” Here, we’re seeing the sky literally, like the universal sky. The weather is what captures our attention but it’s not really who we are. At the end of the day, it’s not who we are inside but it still shapes how we see the world.

Cindy Ingram: Oh, I love that quote. I’ve never heard that one before. I think this helps me remember that what you had said too is that we are the universe. Everything that is in me was once stars, planets, and dust. I am now a person because all of those things came together and created me. Somehow, in that process, it created my consciousness, which then allows me to know that I’m a part of this universe and to know that I’m part of the sky. It puts your day-to-day issues into perspective.

Madalyn Gregory: It’s interesting to me because I love that it’s Carl Sagan that said we are all star stuff or whatever but I also like the fact that every time you drink a big glass of water, statistically, at least one of those little water atoms in there was dinosaur pee at some point.

Cindy Ingram: I didn’t know that.

Madalyn Gregory: It sounds like a really weird thing but it makes it mundane at the same time. It’s like this huge, universal, big, majestic, amazing life that we’re living but also like dinosaur pee. I’ve gotta get my kid to rehearsal. I guess it’s the duality of life because we can’t always be in this celestial headspace because that’s just not what life allows but also, it’s beautiful. I like the dinosaur pee. It’s real. It’s true. It’s just like life is messier. Even here in the stars that we see through his eyes, I don’t know all the terms but there’s some cloudy birth of a new planet.

Cindy Ingram: Nebula.

Madalyn Gregory: Yeah. There are new things happening there but that’s a very violent process in the universe. That’s not something calm and meditative. That’s like a lot of explosions—it’s probably not explosions—but stuff had to happen, stuff had to crash into each other and burn. I think it’s messy. I see that here. You talk.

Cindy Ingram: I’m just sitting here like, “Oh, Madalyn is so good.” Something I’m also noticing too, you’re talking about the complexity of space and how it’s not this blue space with dots on it, that all of those are light from a long time ago, explosions from a long time ago, all this tumultuous stuff happening in the universe but it is so complex and it’s chaotic, but then also, it makes me think of how complex we are and our bodies are. I think that shows that here, you have the little tube-looking things above his eyes, which are like an eyebrow shape but to me, they look like maybe optical nerves or veins or something, then they have these lines coming off of them. To me, they look like they could be representing nerves, but the inside of us and the whole complex system of our bodies are so complicated. We don’t have to do anything. I’m just here. I’m alive. I’m breathing. My heart is pounding. I’m talking. I’m thinking. My body is just letting all that happen. It’s a thousand different things. A million different things are happening in my body right now to allow this conversation to take place.

Madalyn Gregory: I think that’s a really good point that we can look up at the sky and we just see the pretty stars that have come to us. We don’t see everything that had to happen to make that happen. Just like we don’t see everything that’s going on in our bodies unless something starts to hurt or do something it’s not supposed to. We’re just not aware of it. I see that in the artwork too. We talked about the corrugated cardboard edge. I think like what do the lines represent? Are there nerves? There are also these lines that are coming up from his mouth that because of the way they’re angled, they almost look like Roman numerals but they just are like little “i” shapes or capital “I’s” I guess. But I feel like everything has a metaphorical meaning happening because three of the teeth are missing, what does that represent? Is that something more from the artist specifically? But even then, is that the wounds or is that the pain that has happened? Because it’s hard to see that.

Cindy Ingram: To me, it looks like he is broken in many ways. He’s got the missing teeth. Above his mouth, there are these white things that come together, then there’s these little blue lines that look like stitches. That part is sewn together. Then maybe those Roman numerals could be like staples or something. It almost looks like he’s not this perfect pristine fit self. There’s messiness, brokenness, and humanity represented here.

Madalyn Gregory: For sure. One area we haven’t really talked about maybe is like the throat or the esophagus or something but it’s got these little almost like a wave lines that go up toward the mouth. To me, they almost look like steps. It’s making me think like his mouth is open and we see the stars but from the internal space of our bodies, what we hold inside. There are all these unseen processes happening but also, there are all the things that we are aware of that we do think about that we don’t share, we don’t say. It’s just making me think our throat is like a ladder for our voice. We don’t climb that ladder a lot. I feel like those are the steps we have to take to share ourselves because we are all in this encasing, looking out at the world and the only way that we can be in community with others is to actually communicate. I never thought about that community and communicator real clicks.

Cindy Ingram: I see that too, that being his throat. it doesn’t feel like he is going to talk. It feels like he is actively keeping it down. I don’t know what is giving me that impression but to me, it feels like he has something to say but he’s not saying it or doesn’t want to say it or can’t say it.

Madalyn Gregory: It’s very pristine looking. Going back to the 2001 thing, even though it’s complicated and there are broken parts, none of them are bloody. It’s fixed now. We put ourselves back together and we’re whole. Everything’s fine. It feels like he’s not or they’re not allowing that to come out. I think that fits too with the fact that we’re inside of their head because we don’t get that inner perspective. Even whenever we try to communicate, it doesn’t always come out right. It feels like they are trying to be proper. We are just getting insight into what it actually feels like to be inside this person.

Cindy Ingram: Now I’m wondering, depending on who’s looking at this. I want to put 10 people in front of this and see how they feel being in this person because to me, it does not feel comfortable.

Madalyn Gregory: No.

Cindy Ingram: I am not enjoying necessarily looking at this for a very long period of time. I’m enjoying the conversation about art. I think it’s amazing but it is making me feel a certain way. It’s not letting up. It’s just getting me.

Madalyn Gregory: I agree. It’s hard to imagine looking at this and being like, “Oh, that’s cool.” Maybe it’s like Led Zeppelin. Let’s listen to music and have experiences or whatever maybe in that. I feel stressed every time I look at this. I feel like what you were saying earlier about everything that our bodies do and all that, it reminds me that I contain multitudes. Also, there’s that book about all of the bacteria that lives in us. It’s like a very significant part of what our body is. He called it, I Contain Multitudes, which I think is brilliant because it goes back to that mundane and universal thing that’s all co-mingling. It’s not separate. You can’t have one without the other. I feel that in this. It’s like we’re looking at the messy parts that we pretend aren’t messy.

Cindy Ingram: It’s painted very smoothly and very precisely. You can’t really see his brush work. The gradients are just so smooth. That is really interesting to me too because even though he made it so smooth, it does feel so messy.

Madalyn Gregory: I feel like that’s a part of what makes it so impactful is that it is so pristine because I feel like it would be a much different artwork if there were big splotches of color on the canvas or whatever. It just wouldn’t have the same feeling.

Cindy Ingram: It’s funny, when we were talking about what artwork to do today, I suggested this one and you’re like, “Ooh, that one creeps me out.” I was like, “Oh, that makes it good to talk about.” But now I’m like, “Oh, this creeps me out too.” I like it. What do you think about the cardboard situation, why cardboard?

Madalyn Gregory: It’s interesting to me because like life does, I very recently heard something else about this, which was the reason that cardboard has that piece that goes up and down or whatever, it actually adds a lot of strength. The thing I saw was talking about how brick walls could actually be built like that. If you’re not worried about space and stuff, it actually is much stronger. The fact that’s like the edge, that’s like his skin, it’s protecting them from whatever is outside and from all of this turmoil in the universe, and these nebulas that are being born but also the fact that it looks like cardboard, we all know cardboard will come across the country or across the world. Whatever’s inside of it will be safe or maybe it got a little bit wet, then everything’s broken. It’s something that can protect and can contain but it’s not impervious. Even here, it’s opened up.

Cindy Ingram: It’s strong and protective but it’s impermanent. It’s disposable. It’s something that will eventually have to be replaced, which is true of our bodies as well. They are impermanent. We are bags of meat that will eventually become stars.

Madalyn Gregory: Flowers or dinosaur pee.

Cindy Ingram: Dinosaurs probably would come again.

Madalyn Gregory: Yeah, why not?

Cindy Ingram: If not on Earth, somewhere else.

Madalyn Gregory: They’re birds. They’re chickens. That’s true. I think that really is speaking to the fact that this perspective that we’re looking through is temporary. It’s not going to be here. That makes me feel a little bit less freaked out.

Cindy Ingram: I was going to say the same thing. It made me feel better.

Madalyn Gregory: Yeah. The fact that this is open, they are allowing us to look at the universe through their eyes. I feel like there’s always stories, whenever people are close to dying or they’re getting older, where they want to impart knowledge. Advice is the thing that you do whenever you’re trying to make everything neat and better for whoever you’re talking to. It feels less scary because that’s also a universal thing. Everybody goes through it. Everybody dies.

Cindy Ingram: It made me just feel a sense of relief once we started to talk about that. This is temporary. All pain will end eventually, then you will be whatever you believe will happen after you die. I think it’s very soothing. Also, it made me think too that it is a privilege to see through this person’s perspective because we don’t show people our full range of pain, our full range of joy, and our full range of anything because every individual person is so filled with all of their experiences, their trauma, their thoughts. Even if we did try to show it, we can’t ever really fully show who we are to someone else.

Madalyn Gregory: Language isn’t perfect. You can’t be in someone else’s body. I think that’s why Freaky Friday has been remade so many times. Like the idea of walking around in someone else’s shoes literally is scary but how different would the world be? There’s a lot of disagreement in the world, there always has been but whenever it seems to spike, articles and stuff will come out about how to talk to people you disagree with. The biggest thing that they all say is like, “Don’t go in trying to change somebody’s mind.” You have to listen because we don’t listen to each other. If you’re not going to listen, they’re not going to listen. I do really wonder what life would be like if we could just, even for a little while, even in a cardboard box, feel what other people have felt because there’s no good way to do that.

Cindy Ingram: It made me think of this—and this is a really nerdy reference. It’s a reference from someone else—but my husband told me about this video game that he plays. I don’t know the name so I apologize but if you’re just dying to know, you can email me and I can ask him but he says that in the game, you can see other people’s memories. You can step into a character and look around in their memories and then in their experiences and then you can come back to your own character, and he says that it’s the most fascinating thing because it makes him think about what it would be like to do that with another person. It’s like the closest he can get to doing something like that. But everything that the person sees, everything that they think…

Madalyn Gregory: Yeah. I guess it’s the whole nature versus nurture thing. But it’s both and it’s always been both. We can’t account for that. We don’t have an abacus that can be like, “Okay, if you do this and you do this, then this is the person that you–” Even if we could, it’s not clear to us and it never will be. Art I think is one of the only ways to try to experience that.

Cindy Ingram: Yeah. I had another thought about the cardboard. It also I think could be a mask that the artist has created to show the world like we’re seeing the inside of the person but then that cardboard could be what they show to the rest of the world. Maybe it’s showing that it’s not real, it’s fake, whatever they’re portraying to the world is fake.

Madalyn Gregory: Yeah. I think that’s super relatable because I remember, I had this point early in adulthood where I was like, “Am I just lying to everybody all the time? Because I feel like I’m one person with this person, I’m one person with this person. What is wrong with me?” It took me way too long to realize that that’s just being a human and that’s just being a person because the different sides of yourself are going to come out. I contain multitudes and which multitudes are being shown depends on the situation. I think we give ourselves a really hard time for the masks we wear or whatever, but I also don’t know how else we could really do it. I don’t know, maybe with the right people in the right situation, your mask is more representative of the blood and bone beneath.

Cindy Ingram: Yeah. I had a similar moment in my life where I would feel, for a long time, really guilty that I wasn’t telling everybody everything that was going on with me. If I kept something to myself of, “Oh, this is just something I want to think about for me.” I felt like to be an open honest person, I have to share that with everybody and then I would feel guilty about that. Ultimately, it became this weird battle in my head and then I felt I was lying to people by not telling them these personal things. I still do that and I don’t know where that comes from. I have to keep telling myself, “Stop, you don’t need to tell everybody everything.” But it just feels dishonest for some reason.

Madalyn Gregory: Yeah. I think it’s interesting because I’ve also heard people coming at it from the complete opposite side of, “You don’t owe anybody anything. You don’t owe your story, your truth, or any of that.” I think I still do have at least a little bit of a battle raging inside because that’s true, I do 100% agree that you don’t owe anybody your life story or whatever, but also I guess it’s just a matter of the masks because trust has to be built and space has to be built for that. There are reasons that we wear masks, because we’ve all been hurt and we’ve all been told things. I think sometimes we don’t even see the masks. We don’t even know they’re there because that takes work to see it and to be able to take it off. Maybe that’s what the artist is saying here. He’s done the work or he’s trying to do the work at least for this specific mask so here, I’m going to take it off and let you look through it.

Cindy Ingram: Oh, yeah. Maybe we’re not looking through his perspective but we’re looking through the masks of this one mask’s perspective. Hold on, I’m confusing myself so no, I don’t think that’s true because then we wouldn’t have the bones. The mask doesn’t include the bones and the veins and things.

Madalyn Gregory: I think it could because, I don’t know how scientifically accurate it is but I think we’ve all heard your cells get replaced every seven years or whatever and so your taste buds change and all this. We are literally physically not the same person we were as a child and as 10 years ago or whatever. We are constantly being renewed. I think it would make sense for the bones and the teeth and the veins and everything to come along. Maybe it’s even more substantial than, “This is the mask I wear around people. This is the person I was.” You still carry that person forward I think.

Just the other day, my teenager was saying, “Oh, my goodness. I know I was like that when I was 12.” I’ve even said every couple of years, it’s like I look back and I hate everything that I was. I feel that’s maybe a little strong but also, I don’t think it ever goes away. I think if you’re not looking back every few years like, “What was I thinking?” that’s a sign of growth, that’s a sign of embracing the change that is always there.

Cindy Ingram: I can relate to that a lot because I have this problem where I think that if I haven’t seen someone in a long time, I just assume they start to hate me, it’s a problem. I’ve always done it. That’s why I’m like, “It’s been a year. Uh-oh, they definitely hate me.” A year later, I’m like, “Oh,” it’s an anxiety problem. But I also then, when faced with talking to that person again after it’s been a long time, I’m like, “Well, gosh, I’m a different person than I was when I saw you three years ago. Am I still going to like you? Are you still going to like me?” I don’t know where I’m going with that but whatever you said just resonated.

Madalyn Gregory: Like you said, what is it going to be? You don’t know until you know. I think that’s why everybody does have that feeling if you’re going to see somebody that you haven’t seen in a long time. Maybe there are some people out there that don’t feel like that but in my experience when I talk to people, that’s something that everybody feels. Sometimes you get there and it’s like no time has passed and sometimes you get there and you’re like, “The switches are not clicking anymore.” I think that’s fine and I think that the hard thing and the scary thing, but the good thing ultimately, is just to keep trying to connect whether it is somebody from three years ago or whether it’s somebody you met yesterday, or whatever. You can’t connect unless you’re trying to connect and you can’t take off your mask and let somebody else hold it or see it or look through it unless you’re actually realizing that you have a mask.

Cindy Ingram: So good but I am going to completely change the subject because I just realized something about this artwork. I got a sense of relief for a bit after we talked about the impermanence of life and cardboard, but I am back to feeling uncomfortable because I just realized I have been looking at this artwork as if it is my father.

Madalyn Gregory: Oh.

Cindy Ingram: He’s been popping in my head the entire conversation, just nuggets here and there. My biological dad was an alcoholic. My mom and dad divorced when I was five and then when I was in the third grade, he disappeared. I didn’t know he was an alcoholic until years later and he would come in and out of my life for a while and then eventually he died when I was in college. But he was missing teeth last time I saw him. He had a rough life. Alcoholism just destroyed his life but he was missing teeth and so I think that’s my main reason that I’m seeing the missing teeth. But then also to just to give you a little bit of information about the artwork, what we know about this artwork is—and I had read that before we had this conversation—it says, “This artwork depicts an inside out view of the artist’s head as he explores the social impact of technology on humanity,” and then it says, “Along with his personal battle with alcoholism.” I had alcoholism on my brain already and I was like, “Oh, I can see that, the alcoholism in the artwork. I can see that.” The reason I can see it is because of the missing teeth and I have that personal connection.

I’m just looking at this. I’ve worked my whole life through the trauma of that experience. I’m not going to sit here and cry about it or anything, but as an adult who has struggled with mental health issues, I look at my dad differently than I did when I was a child. As a child, it was abandonment, it was anger, it was deep, deep sadness. But as I’ve gotten older, I really wish that I knew him, I knew who he was, and I knew what was going on in his head and what his true thoughts and feelings are because now I do know more about alcoholism, I know more about addiction and disease, that it’s a disease. I could never accept that as being a disease when I was younger. That didn’t explain away the pain. That never could explain away the pain of being left and abandoned. But now I look at it and I’m like, “I just want to know what he was like. I want to know what he was thinking.” But I don’t know. So I’m looking at this and I’m seeing this broken toothless, stitched-together person who looks like they’re in a great deal of pain, who looks like they’ve got their voice cut off. That’s how I feel about my dad. I didn’t get to hear his story. I never got to hear his story. When I’m looking at this, maybe I am going to cry about it, but that’s what I’m seeing is I think it is making me feel maybe more connected to him as a person than I typically ever allow myself to think about. There’s that.

Madalyn Gregory: That’s perfect though because that is what we’ve been talking about. We don’t always get that opportunity and even when we do, it’s not always satisfying to know what was happening because I think a lot of people can’t articulate it. Even if we can, it’s not going to be the complete story. What a gift it would be if he could hand you a mask and be like, “This is what it was like.” We don’t get to do that, and like you said, you have to heal yourself to even get to the point where you’re like, “Okay, but what was it like from their side?” I don’t have a great relationship with most of my family. I’ll talk to my grandmother sometimes and one conversation we’ve had again and again is that I want to know more about the family history because it got erased whenever her parents came here and I want to know that. She’s said many times that she’ll send me stuff, that she’ll send me pictures and she’ll write it out or she’ll tell me, “We’ll do this whole thing,” and then it never happens. I know that the years where that will even be possible are getting smaller and smaller. So much is lost and not being able to connect. Maybe if everybody made art. What if every family sat down to dinner and then also made art? I want there to be a way for us to see behind the masks.

Cindy Ingram: Yeah. It’s something I do try with my children. I want to make sure that they see me as human, that they do see that I have feelings, that they do see when I’m hurting. I don’t want them to look at me and just always see this happy mom that just has her sh*t together. I need them to see that it’s okay to be human, it’s okay to have feelings, it’s okay to feel pain, all of these things are okay. Because I feel that is something that I missed out on. I guess I saw the brokenness of my dad, I was too close to it too.

Madalyn Gregory: Yeah. I think it’s a balance for sure because I definitely saw the brokenness of my parents but not in a healthy “I’m going to be real with you, child.” I constantly walk that tightrope with my kids too because people have that story of like, “That’s the moment I realized my dad wasn’t perfect or whatever.” I don’t know if my children had that experience. I hope they didn’t though, especially whenever you’re an authority figure to someone else, it’s very easy to not be vulnerable at all with them or to think that being vulnerable with them is big red X “Don’t do that.” I don’t think that’s true. I think there’s a way to balance it and we’re not always going to get it right because we’re human, but at least trying, I think that’s something that this generation of parents is doing more than, at least, in the US maybe, but we’ll see, but I do think that that’s something that’s happening more and I’m very interested to see how our kids grow up and how their kids grow up.

Cindy Ingram: Yeah. Oh, so many topics in this artwork.

Madalyn Gregory: I know. I like the few things that it could bring around the edge too because for the most part, it’s very even, but the thing that keeps ringing in my head is if you look at the evolution family trees that they’ll do, that’s a circle and it comes out and there’s a line for that species and that species and they all branch off the tree, it makes me think of that, the tree of life or the bush of life depending on which one you’re looking at, but they all have all the lines. It makes me think that all those lines are, I’ve heard John Green say this, I don’t know if it’s actually from him though, but he talks about all the people that loved him into being. There are people that loved us into being and there’s people that affected us maybe not with love, but all of that and all the star stuff, I feel like that is everything converging to make this.

Cindy Ingram: Oh, I love that. I don’t have anything to say other than I’m just now I’m looking at it through that lens and I think that is so neat. Let’s talk about the title.

Madalyn Gregory: Yes, it has a good title. It’s so good.

Cindy Ingram: When I’m sharing artwork with students, I don’t ever tell them the title until after we’ve had the conversation because I don’t want it to sway what they’re thinking but this title is called The Anguish of Being and the Nothingness of the Universe.

Madalyn Gregory: Dang. I’m a little bit depressed just hearing it but it’s so good.

Cindy Ingram: But it fits exactly what we’ve been talking about, the anguish of being. Being a person is hard. The human experience is hard. I was watching the Oprah and Prince Harry series they did on mental health, it’s called The Me You Can’t See, and they chronicle different people’s mental illnesses. I’m about halfway through, I think there are seven episodes, but Lady Gaga was on there and she’s talking about her trauma she experienced after being raped and all of her mental health issues. They were like, “What was going on in your life while you were experiencing all this pain and depression and stuff?” She’s like, “I won my first Oscar.” She’s like, “People look at me and I have privilege and I have money and I have all of this stuff,” I forgot who said it in the show, but it was, “The human experience still applies or the human existence still applies.” No matter who you are in any walk of life, wherever you are, you’re still human. The anguish of being is still hard.

Madalyn Gregory: Yeah. Goodness, even that title ties in perfectly, The Me You Can’t See. Where does all of that come from? Is it just that we’re so alone that we’re trapped in our own heads? What causes the human condition?

Cindy Ingram: Yeah. When did it start? Did cave people, did paleolithic people have anxiety?

Madalyn Gregory: I mean, they were out there making their art and telling light shows. I bet they did.

Cindy Ingram: I feel like they did. Our brains are the same.

Madalyn Gregory: Yeah. They didn’t have to deal with the technology that he’s talking about in this artwork but also they were having to run from creatures that were trying to eat them. It’s like what’s the cure for the human condition, let’s solve this on this podcast. It’s so sad that it’s so universal but it’s also comforting in a way, but also we just have to do the little things that we can do to make it better however we can. At least we’re talking about it now. It didn’t get talked about before.

Cindy Ingram: Yeah. I like that, the doing the little things. I’m looking back at the artwork and earlier, I was thinking, I didn’t feel like there was a lot of hope in this picture at the beginning. To me, it was just I was feeling stressed about it. I didn’t see a lot of hope. But now that I’m looking at it through the lens of, “Okay, we’re all experiencing this anguish of being.” Our main job is to find those moments of joy, the things that bring us peace and happiness. Maybe the areas where he is stitched together in the artwork and the little burst of light on his forehead, the ability to see the vastness of space and experience it and sense it through just having five senses, it’s pretty awesome, or more than five. Now I’m starting to see there’s more hope here and he’s alive and he’s here, which it’s hopeful in itself.

Madalyn Gregory: Yeah. The stitches that we talked about earlier, they show that he had pain and brokenness, but also it shows the possibility for healing and for coming back together and just being able to go on. I feel like that’s something that I’m still recognizing in life. The change is constant and the pain is always there in one way or another, but as far as we know, there’s no other way to live, there’s no other way to be in this world without having that. We have both things, we have all the things. I think that’s interesting that it’s the nothingness of the universe because we can look at the universe at large and think it’s so empty, barren, and scary but it’s both. That’s what we’ve been talking about the whole time. It is anguish but it’s also ecstasy. I feel like a lot of the language that we use to talk about this stuff is turned into platitudes. You can’t have the good without the bad. I feel like I hear people’s stories of going through a life-changing experience whether they’re talking about it or a book or whatever. There’s always this clarity that comes with just accepting the fact that you’re not ever going to have all great positive days.

Like the quote earlier, you’re the sky and everything else is the weather. Finding that core within ourselves that exists regardless of the masks and regardless of the anguish, that’s all we can do, but also maybe that really is enough even though some days it doesn’t feel like it. I don’t know that we’ll get another choice though.

Cindy Ingram: No. I don’t think so.

Madalyn Gregory: You can make it enough or not. What good does that do? What good does it do to feel like it’s not enough? It doesn’t. So we might as well say that it is.

Cindy Ingram: In the end, you’re impermanent. In the end, you’re infinite at the same time. No matter what happens, that remains true so we have to do everything we can to feel at peace with that I guess.

Madalyn Gregory: Yeah.

Cindy Ingram: I think that’s a good ending. Knowing us, in 10 minutes, we’ll realize we forgot something really big. That happened last time but I don’t think there’s a lot of race gender issues necessarily here that we need to talk through. I think we’re good.

Madalyn Gregory: It’s on the other side of the mask.

Cindy Ingram: Yeah, that’s the other side. You’re right. All right. We have a lesson for this artwork in our membership, The Curated Connections Library, a complete lesson with activities, discussion questions, information, powerpoint, worksheets, video. You can see that we spent an hour talking about this artwork through a lot of different lenses and I know that you might be listening and thinking, “Well, these two people spend a lot of time talking about art so my kids can’t come up with this stuff,” but I guarantee you that your students will surprise you. If you show them this artwork, you talk to them about these issues, it will resonate with them, they will have lots to say, and it will be really a profound experience. You can check that out at The Curated Connections Library. If you’re not a member, you can join at artclasscurator.com/join. Thank you again, Madalyn, for joining me today.

Madalyn Gregory: Yes. I always love it and it always surprises me.

Cindy Ingram: Yes. In the best ways possible. Thank you all. I’ll see you next week.

When you’re a teacher, one thing is certain, the lesson planning never ends. The Curated Connections Library is here to help with hundreds of art connection lessons and activities. Our signature SPARK Works lessons include everything you need to teach an artwork every single week. Each lesson features one diverse and captivating work of art and is complete with discussion questions, engaging activities to create deeper art connections, and related art project ideas. With unique worksheets and PowerPoint presentations, every lesson is classroom-ready. Get your free SPARK Works lesson and take a break from lesson planning by going to artclasscurator.com/freelesson.

Thank you so much for listening to The Art Class Curator Podcast. If you like what you hear, please subscribe and give us an honest rating on iTunes to help other teachers find us, and hear these amazing art conversations and art teacher insights. Be sure to tune in next week for more art inspiration and curated conversations.

Free Lesson!

Get a Free Lesson Sample

Get a free lesson download!

Members of the Curated Connections Library get nearly 200 SPARKworks lessons that include everything you need to implement an artwork a week experience in your classroom! Click the button below to get a sample SPARKworks lesson–it includes a lesson plan, PowerPoint, and supplemental worksheets/handouts.

Subscribe and Review in iTunes

Have you subscribed to the podcast? I don’t want you to miss an episode and we have a lot of good topics and guests coming up! Click here to subscribe on iTunes!

If you are feeling extra kind, I would LOVE it if you left us a review on iTunes too! These reviews help others find the podcast and I truly love reading your feedback. You can click here to review and select “Write a Review” and let me know what you love best about the podcast!

Leave a Comment